If you’re like most cyclists, now is what we call the “shoulder season”, “transition phase”, or the “off season”. It’s a time where we may be consuming a few more calories, enjoying watching all of coverage of the cycle tours we missed over the summer, and possibly frequenting the breweries a little more than usual (not that I am advocating for increased visitation to breweries).

But as a very experienced and wise old coach once told me, now is the time to be proactive, not reactive. Now is the time to plan and prepare for the upcoming season especially if your A events are scheduled this summer. The beginning of a season is a new opportunity to reflect on what went well and what didn’t in seasons past. Whether it be looking back on the results of your goal events, workouts, or just your day to day planning, all this information provides valuable insight as you plan for your upcoming year.

So the questions becomes for many athletes this time of year, “What is the best way to plan for the up and coming season?”

We can learn a lot from our fellow athletes so case studies are always valuable tools. Let’s see how another athlete analyzed his previous years’ training using what I call a “Lessons Learned” approach to annual race planning.

Lesson #1 : Review Last Year’s goals, determine if they were met, and if not ask yourself why?

At the beginning of every season, an athlete we’ll call “Bob”, begins by setting season goals and objectives. Without them, Bob knows he has nothing to measure. In Bob’s case, his goals always include a race result, a personal finishing time to beat, or a new training strategy to implement. Bob then sets objectives around these goals. These objectives usually address what he knows as his limiters. Bob then reviews these goals and objectives weekly as he plans his workouts for the weeks leading up to his A race

Bob’s last season goals were to:

- Finish the Whiskey 50 Mountain Bike Race under 4 hours.

- Place top 5 in the Big Sky Biggie (another 50-mile marathon race).

Bob determined that his limiters were his VO2Max and Threshold power. Bob made the personal decision to incorporate VO2 max workouts weekly into winter workouts and focus solely on increasing his max 20 minute power. Specifically, Bob’s objective was to Increase his Functional Threshold Power (FTP) by April (the Whiskey 50) with hopes of increasing muscular endurance and stamina. Due to limited time, Bob also decided to incorporate VO2Max intervals before the Whiskey. From his previous experience, Bob determined that these were the two limiters, and if trained, would make him successful for the Whiskey 50.

As Bob reviewed his 2018 season, he learned that he met his objectives of reaching his maximum 20-minute power by his first A race, the Whiskey. Bob also continued to increase power in each of his VO2Max workouts. However, Bob ended up not meeting his four-hour goal of completing the Whiskey 50 (Bob’s finishing time was actually 4:30). As Bob reflected on his result and possible reasons for not meeting his 4-hour goal, he realized that the training objective he selected did not necessarily met the specific demands of the race itself. Bob learned that specificity in training is critical for marathon mountain bike racing. Increases in 20-minute power and replacing long endurance focused workouts for VO2Max intervals did not yield the specific adaptations necessary to allow Bob’s body to meet the demands of the race course. As Bob planned the 2019 year with his coach, they both agreed that utilizing his time completing workouts and rides focused on increasing late stage power, fatigue resistance, and muscular endurance will be required to simulate the climbing demands that are required of the Whiskey 50. Now that Bob has a Whiskey 50 under his belt and was able to track his power during the race he determined that a new objective for 2019 would be to track 60, 90, and 120 minute power and not spend as much time working on VO2Max.

Lesson #2 – Select your A races carefully considering timing needs for periodization and ability to achieve the training demands required.

Bob had always wanted to do the Whiskey 50 and he had decided that this would be his A priority event. The Whiskey 50 is typically held at the end of April. Bob planned his season to peak and be in top Form for this race. Bob then expected to be on Form again by August’s priority A race, The Big Sky Biggie. Bob trained consistently and on target up until the Whiskey 50. Bob lives in the Northern Hemisphere, where the days are very short and the temperatures are very cold. December was unusually a hard snow month. As a result, Bob spent lot of time on his trainer and little time outside riding his mountain bike.

Bob found it very difficult to develop the specificity of training he knew was required to meet the demands of the Whiskey 50. Bob fit in many sweet spot workouts during the week and attempted to complete longer road rides during the weekends. However, these longer rides were difficult when it was snowing so Bob often substituted skate skiing for long endurance bike rides. As Bob reviewed his notes and reflected on the results of the Whiskey 50, he remembered how difficult it was to keep the pace on such a long race. Looking back, Bob, ended up sick several times during the winter and he tried to cram a bunch of base training in the month before the Whiskey 50. After the race, Bob went back into a base and build approach for all races leading up to the Big Sky Biggie 50. Bob found himself more fatigued after his C races which lead to additional illness in July. Bob also found that his FTP and 60-minute power decreased during the summer up until the Big Sky Biggie 50. Bob had an average result on the Biggie 50 (4th out of 20 in his age category and 23 out of 64 overall). Bob learned that attempting to peak for an early season race like the Whiskey 50 was difficult especially when trying to match the specific training demands of the race living in a winter climate. Bob also learned that A races that are spread to far apart can make peaking and planning more difficult. Bob incorporated to many builds and peaks, leading to excessive fatigue, a loss in aerobic capacity, and fitness by the time the Big Sky Biggie race came around in August. For the next season, Bob and his coach determined that he would select A priority races that were later in the season and possibly closer together. This would allow Bob and his coach to ensure the appropriate ramp rate, build and peak for his training.

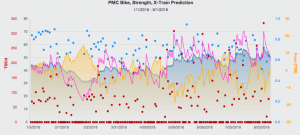

Lesson # 3 – The importance of understanding and using leading and lagging indicators in the Performance Management Chart (PMC) and using those for the coming year.

Bob had a lot of great information to provide to his coach as they were planning for the upcoming season. Bob’s coach was able to take Bob’s information and apply it to an analysis of Bob’s performance management chart (PMC). Bob’s coach specifically reviewed the ramp rate, Acute Training Load (ATL), Chronic Training Load (CTL), and Training Stress Balance (TSB). Bob’s coach determined that Bob was not entirely on Form as he should have been for the Whiskey 50. In fact, it appeared Bob peaked two weeks prior to his races. The PMC visually depicts a decrease in CTL from the beginning of January to February. This loss of fitness was due to decreased training load only 3 months before the Whiskey 50. Later, the ramp rate increased for a short period of time, confirming that Bob was making up for decreased volume early in the season resulting in higher than normal ATL. As Bob had stated earlier, he was making up for lost time. Bob’s coach determined that by the date of the Whiskey, he was rested but his TSB was only at 2 where an ideal range for Bob would have between in the 10 to 15 range. From Bob’s power profile, it appears Bob’s 20-minute power did increase but his 60 minute power and greater decreased. The VO2Max workouts Bob implemented were doing their job, however this could have been at the cost of his preparedness for marathon racing. Bob’s coach also found that Bob was peaking two weeks earlier than he should have for his Whiskey 50 race. From this information, Bob and his coach are confident they will take the lessons learned and apply it to Bob’s current plan, especially if he decides to do another early season A event like the Whiskey 50.

Conclusions:

Planning for a season can be difficult and time consuming. Effective planning means having the ability to subjectively and objectively review your previous season, determine what was successful or not, and then using those lagging indicators to confirm your initial assessment. You then determine leading indicators and adjust your up and coming season accordingly. The process repeats itself yearly and through appropriate training and racing experience, those small tweaks create big gains. This is the art and fun of training and racing.